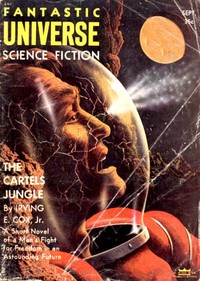

It was a world of greedy Dynasts—each contending for the

right to pillage and enslave. But one man's valor became a

shining shield.

It was blazing hot in the noon sun, and he considered

chartering an autojet to the city, as he always had before. But though

a jet was faster than the monorail it was also more expensive. Acutely

mindful that he had left the service and would earn no more juicy

credit bonuses, he took the monorail instead.

The monorail shot up toward the Palms-Pine pass of the San Jacinto

Mountains. From the crest of the grade Hunter could look back at the

flat, cemented field of the spaceport and the ragged teeth of the

launching tubes rearing high on the Mojave. Ahead of him, misted by

the blue haze of industrial smog, was Los Angeles, the capital city of

Sector West—and indirectly the capital of the entire planet.

Each of the eleven sectors into which the Earth was divided was

controlled by one of the two cartels, as an agricultural or industrial

appendage of the western metropolis. It was a paternal relationship,

although no comparable city had been permitted to develop and company

mercenaries policed the sectors.

Children who exhibited any spark of initiative or ability were skimmed

off from the hinterland to Sector West and thrown into the competitive

struggle of the general school. If they fought to the top there, they

were integrated as adults into the hierarchy of the cartels

Essential plants, naturally. Everything was always essential, and

government spokesmen always made pretty speeches deploring the

situation. It was a pattern familiar to Hunter for years. One of the

cartels would pay Young to strike factories belonging to the other.

Then a second bribe, paid by the struck cartel, bought off the strike.

Occasionally a sop of bonus credits had to be dished out to the

faithful.

I wasn't thinking of technology, Captain. Civilization isn't

machines. It's people. Our accumulation of knowledge is tremendous,

but essentially it means nothing because we know so little about

ourselves. It's absurd to talk of making something better until we

really know the individual we're making it for.